G

iacomazzi

CR

et

al

.

286

R

ev

A

ssoc

M

ed

B

ras

2015; 61(3):282-289

inal pelvic ultrasound, urinalysis, and blood work every

3-4 months and whole-body and brain MRIs once a year

(Table 3). This protocol was designed for subjects with

high-penetrance

TP53

mutations, such as the DNA-bind-

ing domain mutations.

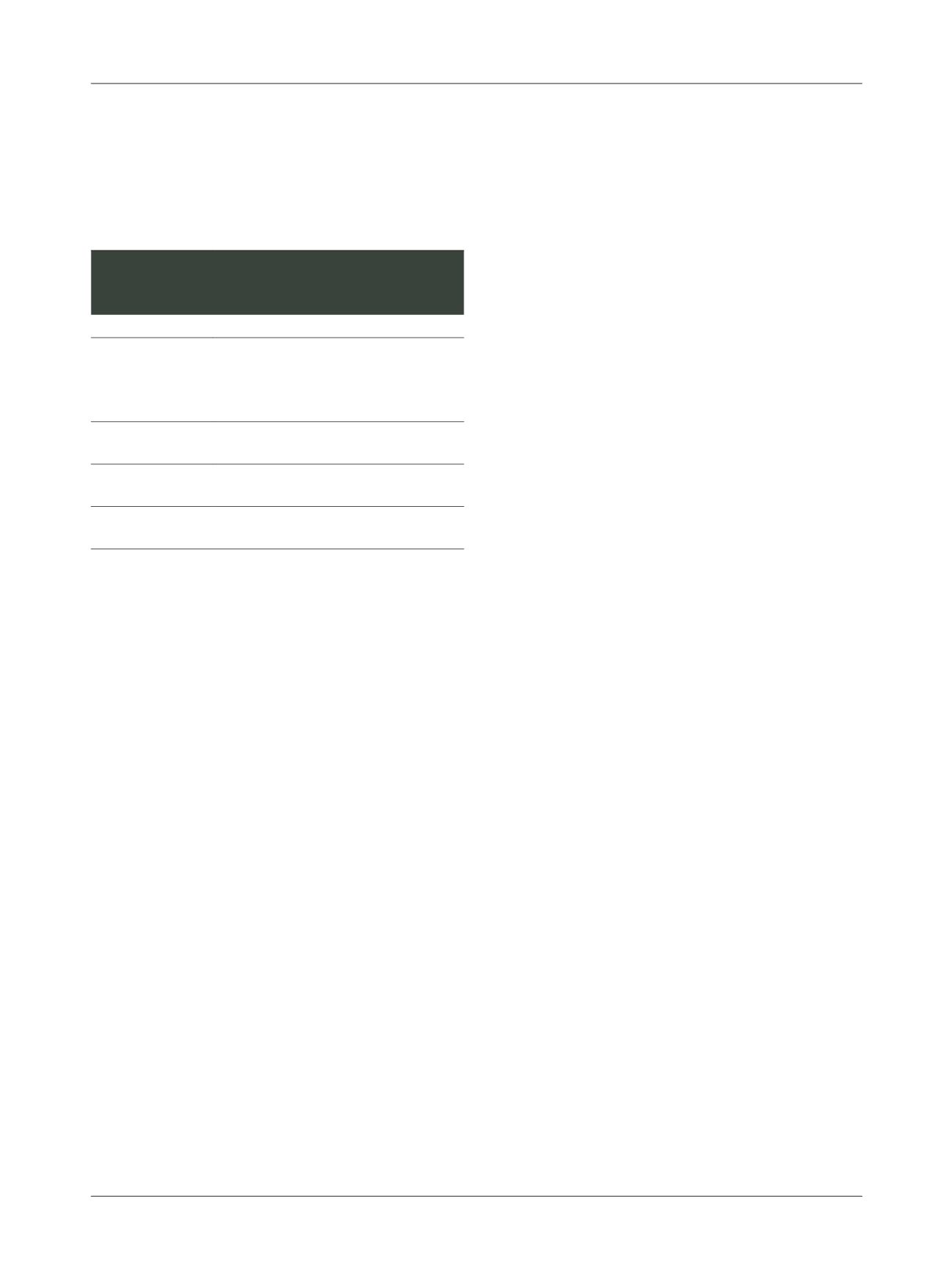

TABLE 3

Proposed screening strategy for asymptomatic

carriers of germline

TP53

mutations affecting the DNA-

binding domain.

Tumor type

Screening strategy

Adrenocortical

carcinoma

Abdominal ultrasound every 4 months

Urinalysis every 4 months

b

-hCG, AFP, 17OHP, testosterone, DHEAS,

androstenedione, ESR, LDH every 4 months

Central nervous

system tumors

Whole-body MRI once yearly

Bone and soft tissue

sarcomas

Whole-body MRI once yearly

Leukemia and

lymphoma

Complete blood count every 4 months

17OHP: 17-hydroxyprogesterone;

AFP:

α

-fetoprotein;

b

-hCG: beta-human chorionic gonadotropin;

DHEAS: dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate;

ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate;

LDH: lactate dehydrogenase;

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

Source: Villani et al. 2011.

40

Psychological aspects

Pre-symptomatic genetic testing of children and adoles-

cents is indicated whenever preventive interventions that

require initiation before adulthood are available.

43

One

of the concerns of predictive testing in cancer genetics,

especially among children, are potential psychological

adverse events.

Currently, the psychological effects of intensive can-

cer screening in

TP53

mutation carriers are not clear. How-

ever, results from preliminary studies are encouraging

and report psychological benefits from adherence to in-

tensive screening practices in LFS families.

44,45

The risks

and benefits both of revealing and of withholding a clin-

ical or molecular diagnosis of cancer predisposition have

been the subject of extensive debate in the literature.

46-48

Psychological harm may be involved in issues such as in-

creased worry about cancer risk, the need for periodic lab-

oratory and imaging tests and the anxiety that precedes

and follows them, and the burden of testing itself. Some

studies have found that a passive, pessimistic coping style,

low social aspirations, and precarious social support net-

works also have a negative impact on mutation carriers,

as does negative perception of the disease and the risk of

cancer itself.

49

However, during counseling of at-risk chil-

dren, these psychological vulnerabilities can be identified

before any diagnostic or therapeutic measures are taken,

thus enabling prevention and mitigation of adverse psy-

chological reactions.

50

Whenever possible, predictive genetic testing should

be performed when the child has a bare minimum of ma-

turity and understanding as to the nature of decision-mak-

ing and its implications. In other words, as children’s in-

tellectual and psychosocial skills mature, they become

increasingly capable of communicating and taking part in

decisions that affect them.

43

Most authors believe that pre-

dictive genetic counseling and follow-up of minors is jus-

tified by the high risk of cancer in LFS/LFL and by the prov-

en benefits of intensive screening.

17,42

When predictive

diagnosis is justified in children who are not mature

enough to take part in the decision-making process, the

child’s parents must be supported throughout the testing

process and also later on, when information regarding can-

cer risk is disclosed to the carrier child or adolescent. The

literature has shown that adolescents and young adults

usually regard genetic counseling as an opportunity to

know the risks of hereditary cancer and support decision-

-making on aspects such as marrying and having children.

51

Several studies show that families with LFS/LFL tend to

trust and comply with genetic counseling, as they feel saf-

er when educated on the disease and able to understand

the diagnosis and better cope with its outcome.

43,50

Genetic counseling of LFS/LFL and bioethical aspects

Genetic counseling for hereditary conditions is an edu-

cational activity that enables the exchange of informa-

tion between professionals and patients (and, as neces-

sary, their relatives). When properly informed, patients

and their relatives are empowered to make better deci-

sions.

52

Decision-making capacity is also related to indi-

vidual psychological and moral development and to is-

sues of voluntariness. The patient’s affective relationships

and personal system of values and beliefs are key elements

in this process.

53

From the patient’s standpoint, at least four factors

must be taken into account during genetic counseling:

the availability of choices; potential cognitive biases in

the presentation of these choices; embedding of a partic-

ular decision within a broader moral framework, such as

the patient’s involvement with other family members;

and the patient’s own concerns.

3,54

One bioethics issue is at the core of genetic counsel-

ing: conflict between the moral duties of warning family

members of genetic risk

versus

the patient’s right not to